Newfoundland

Before 1949, Newfoundland was called Dominion of Newfoundland and was part of the British Commonwealth . In 1949, it became a Canadian province.

The first non-stop flight eastward across the Atlantic.

The book « Our transatlantic flight » tells the story of the historic flight that was made in 1919, just after the First World War, from Newfoundland to Ireland. There was a 10,000 £ prize offered by Lord Northcliffe from Great Britain for whoever would succeed on the first non-stop flight eastward across the Atlantic.

A triumph for British aviation

Sir John Alcock and Sir Arthur Whitten Brown , respectively pilot and navigator, wrote the story of their successful flight in this book which was published in 1969. The followings are pilot quotes from the book : « For the first time in the history of aviation the Atlantic had been crossed in direct, non-stop flight in the record time of 15 hours, 57 minutes. » (p.13) « The flight was a triumph for British aviation; the pilot and navigator were both British, the aircraft was a Vickers-Vimy and the twin engines were made by Rolls-Royce. » (p.13)

As with all great human achievements, a very good flight planning and some luck was needed to make this flight a success. If there was an engine failure during the flight, even if the planning was excellent, there was only one outcome : downward.

In order to make the flight, Alcock and Brown boarded a ship from England bound to Halifax. They then headed to Port aux Basques and finally arrived in St.John’s. There, they joined a small group of British aviators who had arrived a few days before and who were also preparing for the competition. « The evenings were mostly spent in playing cards with the other competitors at the Cochrane Hotel, or in visits to the neighbouring film theatres. St.John’s itself showed us every kindness. » (p.60)

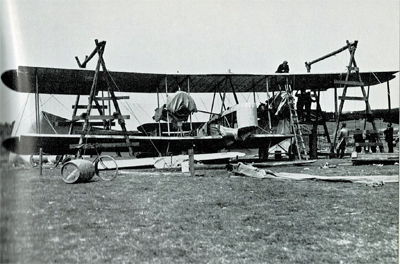

Maritime transport was used to carry the Vickers-Vimy biplane to Newfoundland on May 4th. It was assembled in Newfoundland. « The reporters representing the Daily Mail, the New York Times, and the New York World were often of assistance when extra manpower was required. » (p.61).

While the aircraft was being built, there were more and more visiters coming to the site. Brown says : « Although we remained unworried so long as the crowd contented itself with just watching, we had to guard against petty damage. The testing of the fabric’s firmness with the point of an umbrella was a favourite pastime of the spectators […]. » (p.61)

It was difficult to find a field that could be improvised into an aerodrome : « Newfoundland is a hospitable place, but its best friends cannot claim that it is ideal for aviation. The whole of the island has no ground that might be made into a first-class aerodrome. The district around St.John’s is especially difficult. Some of the country is wooded, but for the most part it shows a rolling, switchback surface, across which aeroplanes cannot taxi with any degree of smoothness. The soil is soft and dotted with boulders, as only a light layer covers the rock stratum. Another handicap is the prevalence of thick fogs, which roll westward from the sea. » (p.59)

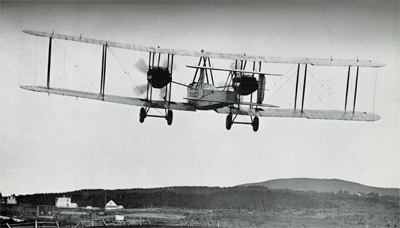

They flight tested the airplane on June 9th at Quidi Vidi. During the short flight, the crew could see icebergs near the coast. They did a second trial on June 12th and found that the transmitter constantly caused problems. But, at least, the engines seemed to be reliable…

The departure

The two men left Newfoundland on June 14th 1919. In order to fight the cold air in flight, they wore electrically heated clothing. A battery located between two seats provided for the necessary energy.

The short take-off was very difficult due to the wind and the rough surface of the aerodrome. Brown writes : « Several times I held my breath, from fear that our under-carriage would hit a roof or a tree-top. I am convinced that only Alcock’s clever piloting saved us from such an early disaster. » (p.73)

It took them 8 minutes to reach 1000 ft. Barely one hour after departure and once over the ocean, the generator broke and the flight crew was cut off from all means of communication.

As the airplane consumed petrol, the centre of gravity changed and since there was no trim on the machine, the pilot had to exert a permanent backward pressure on the joystick.

Flying in clouds, fog and turbulence.

During the flight with much clouds and fog, Brown, having almost no navigation aid, had real problems to estimate the aircraft’s position and limit the flying errors. He had to wait for a higher altitude and for the night to come to improve his calculations : « I waited impatiently for the first sight of the moon, the Pole Star and other old friends of every navigator. » (p.84). The fog and clouds were so thick that at times they « cut off from view parts of the Vickers-Vimy. » (p.95)

Without proper instruments to fly in clouds, they were relying on a « revolution-counter » to establish the climbing or the falling rate. That is pretty scary. « A sudden increase in revolutions would indicate that the plane was diving; a sudden loss of revs would show that she was climbing dangerously steeply. » (p.176)

But that was not enough. They also had to deal with turbulence that rocked the plane while they could not see anything outside. They became desoriented : « The airspeed indicator failed to register, and bad bumps prevented me from holding to our course. From side to side rocked the machine, and it was hard to know in what position we really were. A spin was the inevitable result. From an altitude of 4,000 feet we twirled rapidly downward.[…]. « Apart from the changing levels marked by aneroid, only the fact that our bodies were pressed tightly against the seats indicated that we were falling. How and at what angle we were falling, we knew not. Alcock tried to centralise the controls, but failed because we had lost all sense of what was central. I searched in every direction for an external sign, and saw nothing but opaque nebulousness. » (p.88)

« It was a tense moment for us, and when at last we emerged from the fog we were close down over the water at an extremely dangerous angle. The white-capped waves were rolling along too close to be comfortable, but a quick glimpse of the horizon enabled me to regain control of the machine. » (p.40).

De-icing a gauge installed outside of the cockpit.

Snow and sleet were falling. They didn’t realize how lucky they were to continue flying in such a weather. Nowadays, there are many ways to dislodge ice from a wing while the aircraft is in flight. Here is what Brown says about their situation : « […] The top sides of the plane were covered completely by a crusting of frozen sleet. The sleet imbedded itself in the hinges of the ailerons and jammed them, so that for about an hour the machine had scarcely any lateral control. Fortunately, the Vickers-Vimy possesses plenty of inherent lateral stability; and, as the rudder controls were never clogged by sleet, we were able to hold to the right direction. » (p.95)

After twelve hours of flying, the glass of a gauge outside the cockpit became obscured by clotted snow. Brown had to deal with it, while Alcock was flying. « The only way to reach it was by climbing out of the cockpit and kneeling on top of the fuselage, while holding a strut for the maintenance of balance. […] The violent rush of air, which tended to push me backward, was another discomfort. […] Until the storm ended, a repetition of this performance, at fairly frequent intervals, continued to be necessary. » (p.94)

In order to save themselves, they executed a descent from 11,000 to 1000 feet and in the warmer air the ailerons started to operate again. As they continued their descent below 1000 feet over the ocean, they were still surrounded by fog. They had to do some serious low altitude flying : « Alcock was feeling his way downward gently and alertly, not knowing whether the cloud extended to the ocean, nor at what moment the machine’s undercarriage might touch the waves. He had loosened his safety belt, and was ready to abandon ship if we hit the water […]. » (p.96)

The arrival.

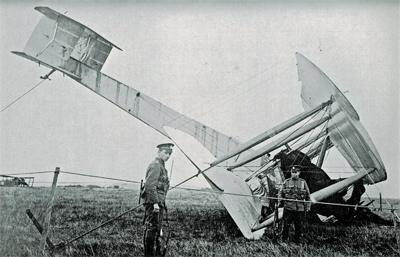

They saw Ireland at 8.15 am on June 15th and crossed the coast ten minutes later. They did not expect a very challenging landing as the field looked solid enough to support an aircraft. They landed at 8 :40 am at Clifden on top of what happened to be a bog; the aircraft rolled on its nose and suffered serious material damages. The first non-stop transatlantic flight ended in a crash. Both both crewmen were alive and well, although they were dealing with fatigue…

Initially, nobody in Ireland believed that the plane arrived from North America. But when they saw mail-bags from Newfoundland, there were « cheers and painful hand-shakes » (p.102).

They were cheered by the crowds in Ireland and England and received their prize from Winston Churchill.

Their record stood unchallenged for eight years until Lindbergh’s flight in 1927.

The future of transatlantic flight.

Towards the end of the book, the authors risk a prediction on the future of transatlantic flight. But aviation made such a progress in a very short time that, inevitably, their thoughts on the subject was obsolete in a matter of a few years. Here are some examples :

« Nothwithstanding that the first two flights across the Atlantic were made respectively by a flying boat and an aeroplane, it is evident that the future of transatlantic flight belongs to the airship. » (p.121)

« […] The heavy type of aeroplane necessary to carry an economical load for long distances would not be capable of much more than 85 to 90 miles an hour. The difference between this and the present airship speed of 60 miles an hour would be reduced by the fact that an aeroplane must land at intermediate stations for fuel replenishment. » (p.123)

« It is undesirable to fly at great heights owing to the low temperature; but with suitable provision for heating there is no reason why flying at 10,000 feet should not be common. » (p.136)

The Air Age.

There is a short section in the book on the « Air Age ». I chose two small excerpts on Germany and Canada :

On Germany’s excellent Zeppelins : « The new type of Zeppelin – the Bodensee – is so efficient that no weather conditions, except a strong cross-hangar wind, prevents it from making its daily flight of 390 miles between Friedrichshafen and Staalsen, thirteen miles from Berlin. » (p.140)

On Canada’s use of aeroplanes : « Canada has found a highly successful use for aeroplanes in prospecting the Labrador timber country. A group of machines returned from an exploration with valuable photographs and maps of hundreds of thousands of pound’s worth of forest land. Aerial fire patrols, also, are sent out over forests.» (p.142) and « Already, the Canadian Northwest Mounted Police [today the RCMP] have captured criminals by means of aeroplane patrols. » (p.146)

Conclusion

The Manchester Guardian stated, on June 16th 1919 : « […] As far as can be foreseen, the future of air transport over the Atlantic is not for the aeroplane. It may be used many times for personal feats of daring. But to make the aeroplane safe enough for business use on such sea routes we should have to have all the cyclones of the Atlantic marked on the chart, and their progress marked in from hour to hour. »(p.169)

Title : Our Transatlantic Flight

Authors : Sir John Alcock and Sir Arthur Whitten Brown

Edition : William Kimber

© 1969

SBN : 7183-0221-4

For other articles on that theme on my website: Aviation pioneers.