(Precedent story: flight service and the Transport Canada Training Institute in Cornwall)

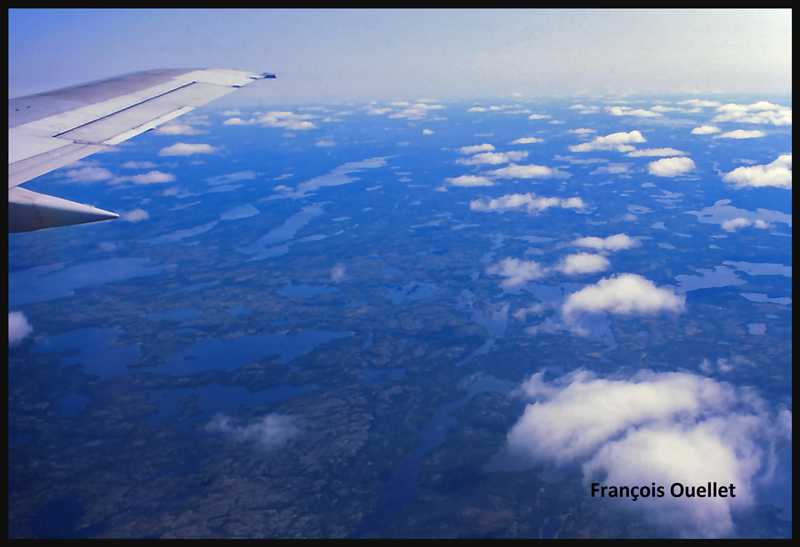

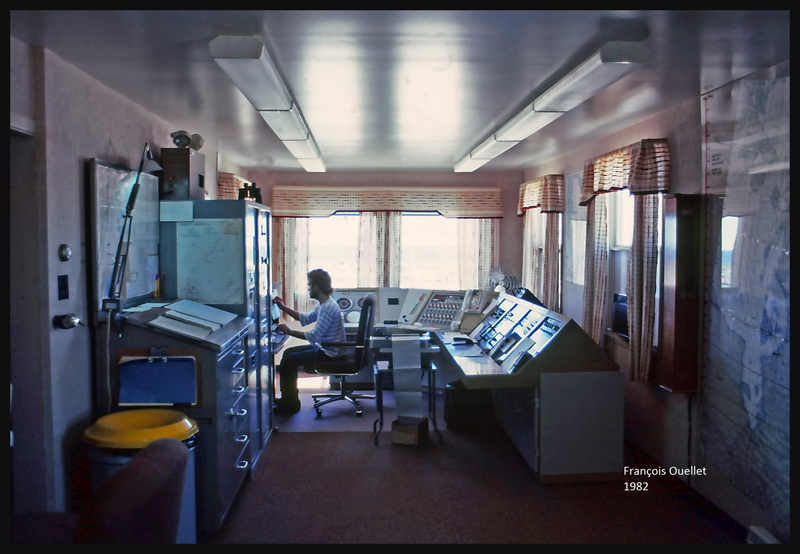

Summer of 1982. Today is the departure from Montreal towards Inukjuak (CYPH), a northern Quebec Inuit village, part of the Nunavik. There, I will start working as a flight service specialist (FSS) for Transport Canada. Nordair’s Boeing B737 takes off and immediately heads northward. It will fly along James Bay and, upon reaching Hudson Bay, will land in Kuujjuarapik, its final destination. From there, an Austin Airways’s Twin Otter will take us over to Inukjuak , an isolated posting further to the north on the east coast of Hudson Bay.

A Boeing B737 landing on the Kuujjuarapik (CYGW) 5000 feet gravel runway uses special procedures. This is a short runway for a loaded aircraft, and braking is less effective than on asphalt. There is no significant margin for error. The wheels must touch as close as possible to the runway threshold, followed by maximum breaking. Passengers really feel the deceleration. The same calculation applies for takeoff: the pilot positions the aircraft close to the runway threshold then applies both the brakes and maximum thrust, and once the appropriate parameters are reached , releases the brakes. As usual, weight and balance, density of the air, airport altitude as well as direction and strength of the winds are all precisely calculated for the aircraft to be airborne before the end of the runway.

After a short stopover, the Twin Otter is now ready for the trip to Inukjuak. The takeoff from Kuujjuarapik goes without problems. I am sitting in the first class section, behind some cargo held by a net. For champagne, I will have to wait for the boxes to be removed from the hallway.

Then a slow descent is started to Inukjuak. From my window, I can see a small group of narwhals. I feel like I’m dreaming but, after a quick research in scientific documents, learn that narwhals can be found in small groups mainly in the north of Hudson Bay.

The aircraft is now getting closer to Inukjuak. The flaps are extended and it is possible to see the runway before the airplane turns on final. It is two thousand feet long and made only of sand thick enough to render its surface unstable.

Upon arrival, someone comes my way with a motorcycle. He offers me a ride to the staff-house, even if there is only a fifteen or twenty seconds walk. I politely declined the offer, but the personage insists. Not wanting to give a bad impression just as I arrive, I finally accept and try to find a small place on the seat of his tiny motorcycle. Hardly have we started to move into the soft sand that the driver loses control of the vehicle. We fall (what a surprise!), but there is no serious consequence. Welcome to Inukjuak!

For more real life stories of a FSS in Inukjuak, click on the following link: Flight service specialist (FSS) in Inukjuak