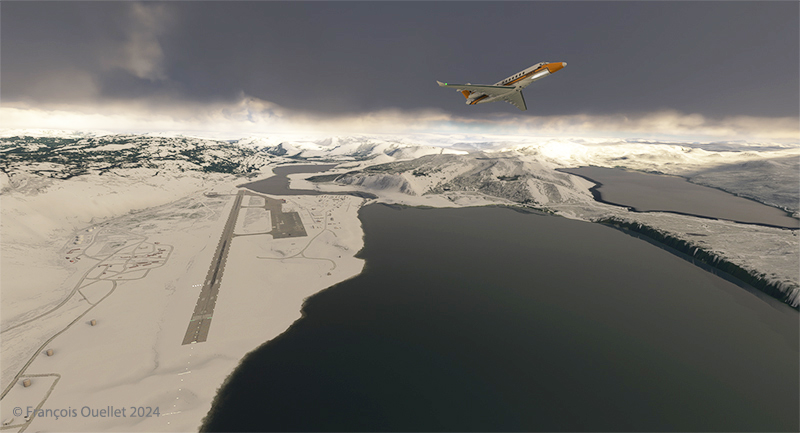

For this second leg of the round-the-world flight simulation, the aircraft departs from Iqaluit (CYFB) in appalling weather conditions, but soon find itself above cloud and approaching an area of high pressure. The sky becomes increasingly clear as I approach runway 09 Kangerlussuaq (BGSF) in Greenland.

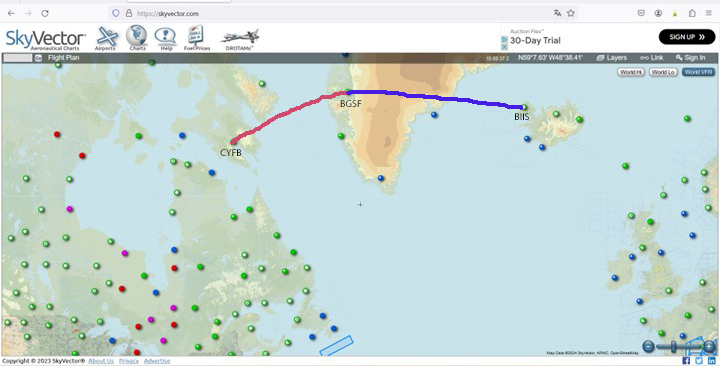

The map shows the planned itinerary: departure from Iqaluit (CYFB), stopover in Kangerlussuaq (BGSF) and arrival at destination in Iceland, at Isafjordur airport (BIIS).

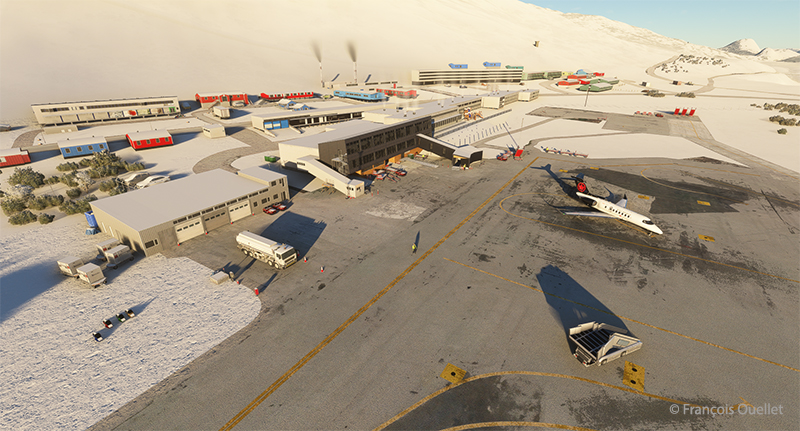

Above, the approach to runway 09. You really need to be well prepared for a destination like BGSF. If the pilot arrives after the tower is closed, the fines are very steep. You can generally expect a little mechanical turbulence on the approach to Runway 09, as the mountains on either side of the aircraft change the airflow.

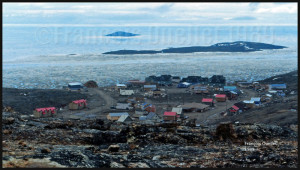

When I worked at the Iqaluit Flight Service Station (CYFB), many pilots would come up to the tower to plan their flight to BGSF. The most frequent problem was the closing time of the control tower in Kangerlussuaq. They knew that a hefty fine awaited them if they arrived late, often due to stronger-than-expected winds or a departure time that was too tight from Iqaluit. Most of the time, they chose to sleep in Iqaluit and leave the next day, rather than force the issue and end up with a $1500.00 bill to pay.

We also had pilots ferrying single-engine planes over the ocean from Europe to America. In this case, the weather had to be excellent, and the captain had to have the necessary equipment on board to attempt (and I do mean attempt) to survive in the ocean in the event of engine failure.

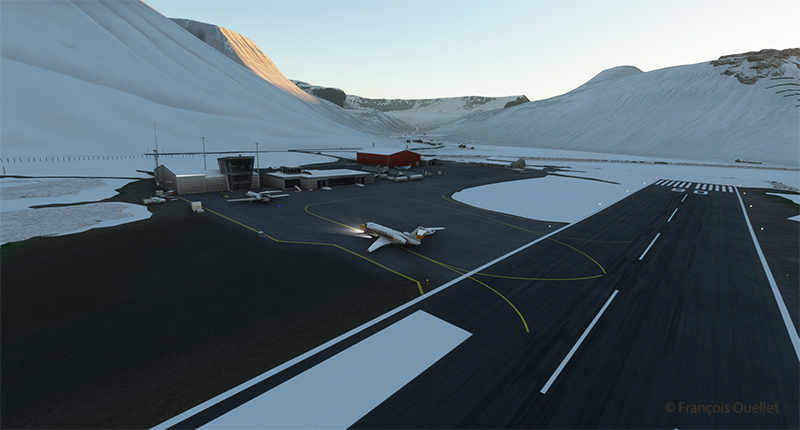

Above, a partial view of Kangerlussuaq’s virtual airport (BGSF), with the Cessna Citation Longitude at a standstill. On the other side of the runway (invisible here), the airport receives military aircraft.

The next day, after a stopover in Kangerlussuaq, it’s time to continue on to Isafjordur. Take-off is on runway 27. The pitot tube heating system and icing protection are activated before entering the cloud layer.

Flying in real weather makes for unexpected screenshots.

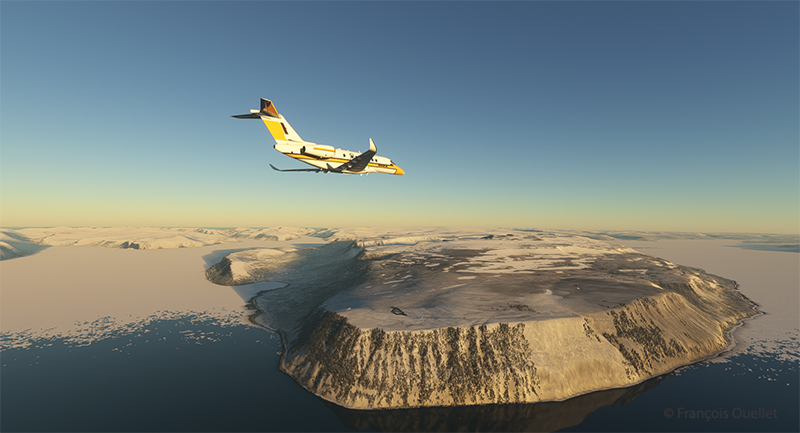

Above, the relief of Iceland shortly before arrival at Isafjordur airport (BIIS). As expected, the sky is clear.

The approach to Isafjordur is demanding, especially when flying a jet like the Cessna Citation Longitude. You have to save extra speed in the sharp left turn to avoid stalling. I made the turn downhill at 160 knots to get to the runway threshold at the right height. Towards the end of the approach, as the angle of the turn decreases, you immediately reduce speed to around 135 knots.

Contrary to real life, it is difficult to have a constant view on a runway when doing a virtual approach in a steep turn. A flight simmer would need 3D glasses to quickly look at the runway and then check the instruments. After two unsuccessful attempts where I found myself a little too high above the runway threshold, I nonetheless managed to land. The instrument panel indicated, however, that the brakes worked pretty hard to slow down the plane, which didn’t really surprise me. There are more relaxing approaches…

The next leg on this trip around the world will be a departure from Isafjordur to Vagar (EKVG) in the Feroe Islands.

Click on the link for more flights around the world in flight simulation on my blog.