(Precedent document: Aviation photography: Rouyn-Noranda aircraft photos during 1986-1988 (Part three of three)

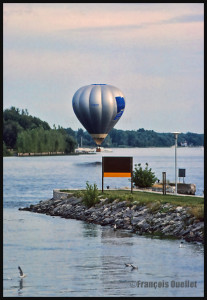

In 1988, I left Rouyn-Noranda for the Transport Canada flight service station, on Baffin Island. Iqaluit is Nunavut’s Capital and a designated port of entry to Canada for international air and marine transportation. Located at the crossroads of both polar and high North Atlantic air routes, Iqaluit airport can handle any type of aircraft.

I had to learn new tasks linked to ICAO responsibilities toward international air traffic crossing the Atlantic Ocean, as well as continue to act as a flight service specialist (FSS) and provide air traffic services.

The departure would be made from the Montreal Pierre-Elliott-Trudeau international airport. I decided to bring my .357 Magnum revolver with which I had been training for several years. Official papers authorized me to carry the gun from my home to the Montreal airport. Once there, I headed to a counter where an agent gave me another document allowing me to carry the revolver in the Nordair Boeing 737 leaving for Iqaluit.

There was no stipulation that the gun had to be left in the cockpit. I went through the security zone. The .357 Magnum was in a small case, in an Adidas sport bag. The bag was put on a moving strap, like any other hand luggage, in order to be checked by a security agent. The bag was not open by the agent; he looked at the screen, saw what was in the bag and that was it. I thought at the time that he might have received special instructions that I knew nothing about.

I was a bit surprised at the easiness with which I could carry a gun, but having never tried it before, since I was not a policeman, I concluded that it was the way things were done when all the papers and requests had been filed accordingly. The screening process being completed, I went outside and walked towards the Boeing 737.

A female flight attendant was greeting all the passengers. I presented her my airplane ticket just as I was ready to board the plane and she immediately asked me if the gun was in the bag I was carrying, and if it was loaded. My answers being acceptable, she invited me to go to my seat.

Once comfortably seated, I placed my Adidas bag under the front passenger’s seat instead of the elevated compartments along the aisles. I wanted to be able to see the bag at all times. The airplane took-off and it was a smooth flight to Iqaluit.

Three years passed and came the time to be transferred at the Transport Canada flight service station in Québec City (CYQB). The world had certainly changed during those three years isolated up in the Arctic. In 1989, Marc Lépine got known for the massacre, with a firearm, of fourteen women studying at the Montreal Polytechnic School.

I headed to the Iqaluit RCMP office in order to fill the appropriate documents that would allow me to carry the gun back to Québec City, a gun that would be sold few months after my arrival at destination. The police officer signed the papers and told me that the revolver would be kept in the Boeing 737’s cockpit.

I asked him, in case it was still allowed, if I had the liberty to carry it in my bag and put it under the front passenger’s seat, like I did for the inbound flight. He looked at me and clearly did not believe a word I had just said. But that did not matter. The gun would travel in the cockpit with the pilots and I would claim it once at destination.

When I think again about this story, almost thirty years later, I realize how the world has dramatically changed. There was a time where I could head to the Montreal international airport with my family to watch the landings and takeoffs from an exterior elevated walkway opened to the general public. From this same walkway, chimney smokers would negligently throw away their still smoking cigarette butts in an area where fuel trucks were operating.

The airport’s management eventually forbid the access to the outside walkway after having received too many complaints from passengers who rightfully claimed that their suitcases had been damaged by cigarette butts thrown from the walkway…

(Next story: Iqaluit and the old American military base)

For more real life stories as a FSS in Iqaluit, click on the following link: Flight service specialist (FSS) in Iqaluit