As the author Herb Boyd writes, « this is the first book to consider black Detroit from a long view, in a full historical tableau. » (p.14). If you are looking for a significant black person that influenced Detroit’s history, he or she is in the book.

The author covers the arrival of Blacks in Detroit through the Underground Railroad the type of work they could find, the music they created, their need to have their own church to avoid racism, the work at Ford, the influence of trade unions, the poor housing conditions, etc.

Of course, there are several paragraphs on racism, police repression and useless violence, the problems caused by the KKK and how a few individuals dealt with it, the Smith Act, the American Civil War and the desire the end slavery, the presence of Rosa Parks in the city and Nelson Mandela’s visit in Detroit in 1990.

There is not only something on the past history and development of Detroit but also thoughts on the future of the city and how it will have to deal with the fact that there are so many people choosing to live in the suburbs instead of in Detroit itself.

Since the fight for equal rights, racism, police repression and the useless deaths of so many black individuals have continued to be an important problem in United States, I have chosen a few quotes from the book on those subjects.

I also chose a paragraph on Nelson Mandela’s visit in Detroit. When Nelson Mandela left United States to fly back to South Africa, his plane had to do a stopover in Iqaluit, in Canada’s Arctic. I was working as a flight service specialist (FSS) at Iqaluit in 1990, so I could see him and Winnie attending an official ceremony in the middle of the night at the airport’s terminal. You can read the real life stories in Iqaluit on my website.

Detroit and Canada.

« In 1795, Detroit was still under British jurisdiction, and the city was a de facto part of Upper Canada. » (p.22)

« Judge Woodward stipulated in a later ruling that if black Americans were to acquire freedom in Canada, they could not be returned to slavery in the United States. “Two of Denison’s children […] took advantage of this ruling by escaping to Canada for a few years and then returning to Detroit as free citizens”. Theirs was a landmark case and would be cited as a precedent in a number of appeals for emancipation by enslaved African Americans. (p.25)

The Smith Act

“The Smith Act, was written so that labor organization and agitation for equal rights could be construed as sedition and treason, the same as actually fighting to overthrow the government by force” (p.162)

Police repression and brutality

“[…] Twenty-five blacks had been killed in Detroit while in police custody in 1925, eight times the number killed under police supervision that year in New York City, whose black population was at least twice as large” (p.112)

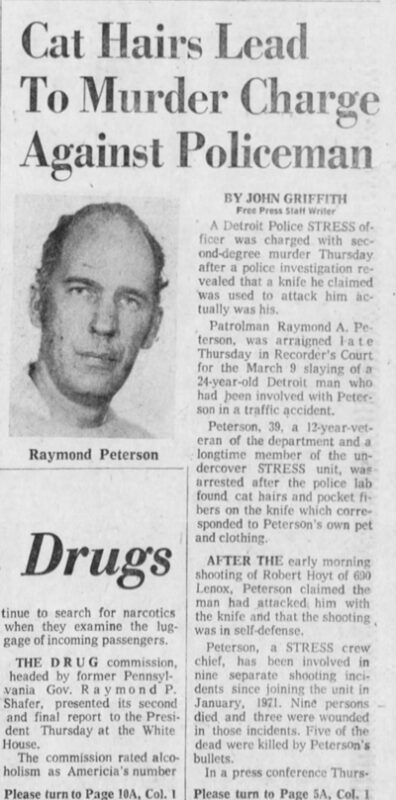

“During STRESS’s (Stop the Robberies and Enjoy Safe Streets) first year as a death squad – cum – SWAT team [near 1970], the city’s police force had the highest number of civilian killings per capita of any American police department. During its three and a half years of existence, STRESS officers shot and killed 24 men, 22 of them African American.[…] Among the STRESS officers, none was as seemingly problematic as crew chief Raymond Peterson. Before he was assigned to STRESS, he had amassed a record number of complaints. During his first two years on the squad, he took part in nine killings and three nonfatal shootings. Bullets from Peterson’s gun killed five of the victims. No charges were brought in any of these cases.” (p.226-227)

© Detroit Free Press March 23rd 1973

“[Around 1999] gentrification was one thing to worry about, but police brutality was a far more menacing immediacy for young black Detroiters. They were keenly aware there was little mercy awaiting them from the police, nor from school conselors or employment agencies, and certainly not from the drug dealers” (p.292)

“[Around 2001] Detroit, according to reports from several local papers, had the highest number of fatal shootings among the nation’s largest cities” (p.300)

“Throughout the nation over the previous decade, from 1999 to 2009, gun violence had taken the lives of thousands of young black men and women, and hundreds of them were unarmed victims of unwarranted police violence. Few of these terrible tragedies were as heart-wrenching as the killing of seven-year-old Aiyana Jones by a police officer in May 2010. It was around midnight and Aiyana was asleep on the couch with her grandmother nearby watching television. Neither of them had time to react to the thud at the door nor the flash-bang grenade tossed into the living room by the police at the start of the raid.

Officer Joseph Weekley immediately began firing his MP5 submachine gun blindly through the window into the smoke and chaos. One of the bullets entered Aiyana’s head and exited through her neck. She was killed instantly. The SWAT team had come looking for a murder suspect who lived upstairs but left with only a dead child. […]. » (p.327-328).

Education

“Ethelene Crockett, having raised three children, earned a medical degree from Howard University in 1942. She completed her internship at Detroit Receiving Hospital, and because no Detroit hospital would accept an African American woman physician, she did her residency in New York City. Finally in 1952, she was accepted at a hospital in Detroit, becoming the first black woman in her field of obstetrics and gynecology to practice in the state.” (p.163)

No middle-class for young blacks.

“With the traditional routes to middle-class success closed, young black Detroiters sought other means of survival, mainly via the underground economy.” (p.254)

Nelson Mandela in Detroit

“In the summer of 1990, Nelson Mandela toured the United States after spending twenty-seven years in prison. […] When Mandela and his wife, Winnie, emerged from the plane [in Detroit], one of the first people they recognized was Rosa Parks. Nelson Mandela stated that Parks had been his inspiration during the long years he was jailed on Robben Island and that her story had inspired South African freedom fighters’” (p.268).

Detroit’s future

“Most Detroiters live in neighborhoods, and in these areas, development is uneven. There are some flashes of improvement, but by and large, communities are still struggling with unemployment, crime, and low-achieving schools. Detroit is a city with large expanses of uninhabited land and is sprinkled with thirty-one thousand vacant and dilapidated houses. In various pockets throughout town, community-based organizations have worked tirelessly to maintain their respective areas against a tide of neglect and disinvestment. The current mayoral administration has tried to use an assortment of methods to arrest the decline of the neighborhoods, with moderate success. This gargantuan task has been assisted with massive aid from the Obama administration, but the city still has major hurdles ahead with a large poor, unskilled, and semiliterate population.” (p.342).

Click on the link for other books on the history of cities on my blog.

Title : Black Detroit

Author : Herb Boyd

Edition : Amistad

© 2017

ISBN : 978-0-06-234662-9